030: making the right choices

one of the many things we can learn from BoJack Horseman in his numerous attempts to get people to love him again

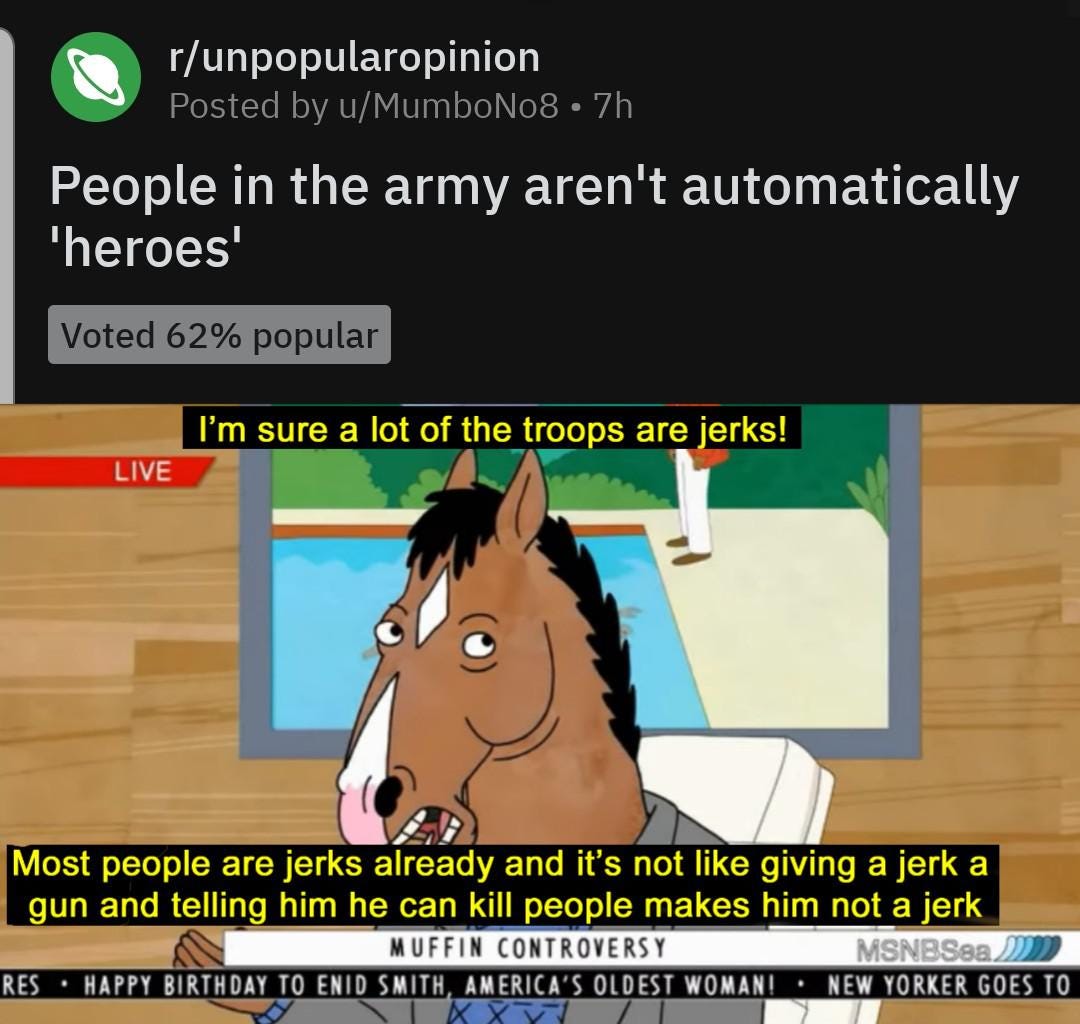

When BoJack Horseman premiered about a decade ago, it was introduced to the general public as a silly adult comedy series starring anthropomorphic characters in the life of our titular character, a 40-something year old has-been trying to make a comeback by writing a memoir of his glory days since, in his words, “This is my last chance to get people to love me again!”1 In the first few episodes, we bear witness to BoJack’s inability to read the room, from inappropriately oversharing the questionable effects of his functional alcoholism on a talk show2, to invalidating the dibs of an army veteran and beefing with him on live television3—the latter being one of the few things BoJack has done that I could actually justify and defend, but that’s for another entry.

The first-time viewer is made to believe that BoJack in his midlife simply pokes fun at how superficial and stupid people are, to which many of us could say in unison, “True dat.” But then the season slowly reveals itself to be something beyond dumb humor that not even the cast saw coming. Later on we learn about Sarah Lynn’s troubled history, a former child star who, alongside BoJack, starred in the hit 90s sitcom Horsin’ Around and has risen to unimaginable heights of fame and disillusionment. We get to know ghostwriter Diane Nguyen, who hopes to find purpose in the work that she does and the relationships she pursues in the ever-vapid Hollywoo, because she would rather be a spectator of its murky tar pit than confront the emptiness of having been estranged from her highly Americanized immigrant family in Boston. Princess Carolyn, an ambitious celebrity agent-turned-manager, is defined mostly by her on and off relationship with BoJack, their longest collaboration together being their shared misery in love (“I have loved you for twenty-five years…”4), and we are challenged to empathize with her dissonance of maintaining the many roles she tries to fill in BoJack’s life. And very reluctantly, we find out that there’s more to BoJack than his superiority complex and his unserious shenanigans that, at the expense of others, preserve his personal interests, most of which stem from the desperation to feel loved.

By the end of Season 1, after BoJack’s first of many benders ends so tragically and he is sobered by the thought that his biggest attempt to feel desired also hurt many people along the way, we see him and Diane Nguyen awkwardly reunite at the rooftop of Mr. Peanutbutter’s house, right after being offered to play Secretariat, the role that he has wanted for so much of his acting career. He delivers this news to Diane who points out how excited he seems for the role. “It’s everything I ever wanted,” BoJack sighs in disbelief. He wonders aloud what he should do now, hoping that Diane does the dirty work of regulating these big feelings.

Diane goes on to say that that’s the problem with life. “Either you know what you want, and then you don’t get what you want. Or you get what you want, and then you don’t know what you want.”

I have always glossed over this aphorism every rewatch because I never saw it that way, let alone believed this. For much of my life I’ve had this belief that either you get what you want and keep at it, or you don’t get what you want and find out other things that you might want. Maybe it is my unwavering optimism caused by reading Rhonda Byrne’s The Secret and getting a little too much into the law of attraction when I was in elementary school, or maybe it is because I was raised by parents who aggressively showered me with enough compliments to make me internalize the belief that I was special enough to live an extraordinary life.

Whatever the reason, it did not occur to me how much confusion I would feel upon growing older, getting to know the person I would become, and noticing how stark of a difference it was to compare the self I’d always imagined to be and the self I turned out to be. I was not briefed about what to do when an internal shift occurs and you become a stranger to these lifelong dreams you had always sworn you would achieve. The last time I ever changed my mind about a significant part of my life was when I gave up on the idea of going to medical school, which I don’t consider much of a loss because it was easy to let go of. By the time I had accepted that I was not willing to put in the work to earn my right to don a white coat and stethoscope hanging on my shoulders, I had something else to project my yearning to. I felt no pressure in figuring out what the right decision was, merely guided by the innocent principle of the right choice being the one that made me happy. Starting a career in mental health was an opportunity that presented itself in the twilight of my university years, and since I began working five years ago, my long-term goal remained steady, even surviving the darkness of the pandemic: gain enough work experience so that I can go to graduate school and become a psychologist.

I am delighted to report that it is finally happening, that I am finally pursuing graduate studies after all these years. And it is in this time of celebration that I cannot help but think of how BoJack must have felt at the rooftop, how exhilarating it must have been to savor the affirming moment of being aligned with your desires. Since I received my acceptance letter, I have been trying my best to believe this fate truly is mine to realize, that this is something I have spent the last few years working toward despite doubting myself along the way. I have been trying real hard to keep in mind that I want this, which scares me a bit, because if I truly wanted this, wouldn’t it be effortless to remember that?

In its six-season stint, BoJack Horseman, the show, has initiated very difficult conversations about substance abuse5 and dysfunctional family dynamics6. I got into the show around the time I had to review for my licensure exam, and there was a period where I rewatched all four seasons just to remember what I was studying. You rewatch it enough times and you notice that many of BoJack’s problems come from the inability to really feel satisfied in what he does and what he gets out of this life. He often finds himself wondering what’s next, worrying about whether there is another chance for him to prove himself worthy or if this is it7.

And he ends up in shambles for the most part, taking for granted the moment that things are working in his favor by either going back to his old ways or trying too hard to embody what thinks is the best version of himself that he comes off too cocky. He gets the role of his dreams, only to be replaced with AI at the end8 because he couldn’t commit to the craft and take himself seriously. He enters a loving relationship for a time9, but when presented with an opportunity to change for the better, he is threatened by conflict and antagonizes the one woman that could have stuck around for much longer. I could go on and on about how things went south for BoJack but that would take me too long to drive the point home.

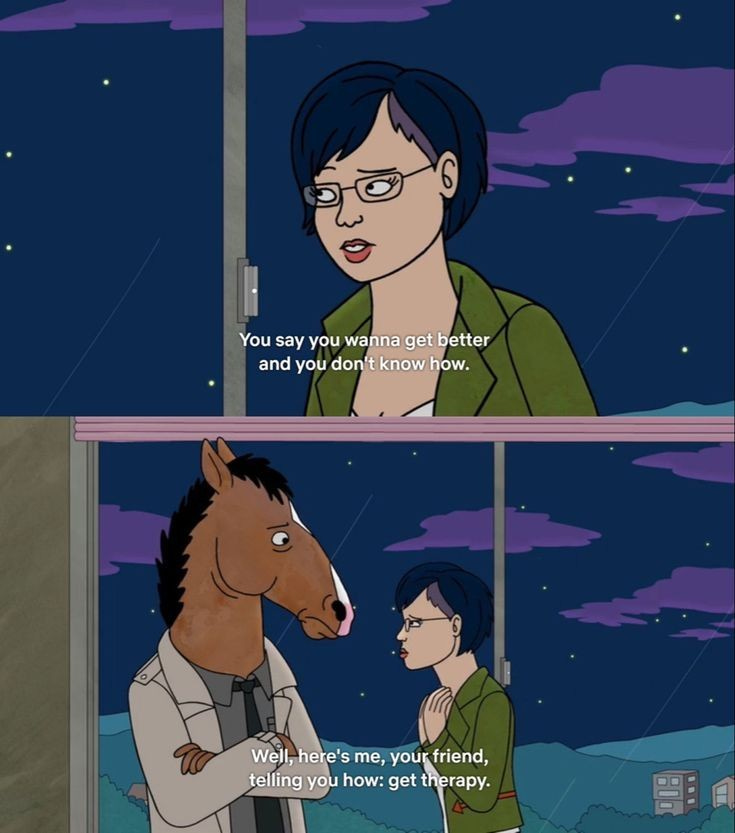

There exists a common denominator in the way BoJack navigates these uncomfortable experiences: he spends so much time in his head. Hell, we even get an episode where we hear the inner monologue that he has to deal with every day10. So much time is wasted idly daydreaming about what could have been, what he could be doing right, and what he could have gone without experiencing in this lifetime. In Season 5, Diane tries to encourage him to seek professional help, which BoJack turns down in a heartbeat. “I’m not someone therapy works on,” he proclaims. “I might be too smart!”11 He claims to be too good at it, the self-awareness required to articulate what his problems are, an essential skill for clients in mental healthcare.

And as much as I have my fair share of criticism regarding the current system of psychotherapy that we practice (Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, I’m looking at you), many people get the wrong idea of eloquence in one’s own dysfunction, assuming that this is the same as high levels of emotional intelligence. If anything, knowing what’s wrong what you and how it affects you only means that you tend to intellectualize your experiences instead of understanding and making space for your emotions. There is nothing clinically impressive about not being able to drive the glaring awareness into action.

Intellectualization is a common strategy used by individuals who like to understand the logic behind their experiences, such as a cancer patient trying to learn more about their diagnosis (and prognosis) so that they could justify the pain that they are feeling, or a young girl viewing her very real, very human experiences of being a teenager from the lens of radical feminism in the hope of learning how she should feel about her unoriginal experiences (which I say in the most loving way possible). When we rationalize our way out of acknowledging how we truly feel, our personhood is reduced to a case study, distancing ourselves from the emotions arising from our current situation and treating this like mere homework to study and understand as an outsider. While there is much to learn about the human psyche, engaging in such a cold practice too much and too soon keeps us disconnected from feeling it out, the very crucial step to getting over anything at all and moving forward.

I tell people all the time that BoJack Horseman is one of my favorite series ever, but I do not recommend any sane person to do a marathon and watch all of it in one go. I’ve found that the best rewatches I’ve had were all slow and calculated, where I would give myself the opportunity to process what happened and get to know how I feel about it. In my recent rewatch sometime last year, I felt like I had outgrown some of the parts that used to hurt, but there were other parts that hit harder this time around. I came to the conclusion that it is because I have done my part these past few years in trying to mend my wounds that the show has perfectly described. At the same time, I was reminded that more work still needs to be done, and that it will always be that way. And it’s not to say that we’re doomed, but that this is probably what it means to be human: to strive for change that allows us to be content with the life we live, and to believe that it is possible to turn things around in spite of it all.

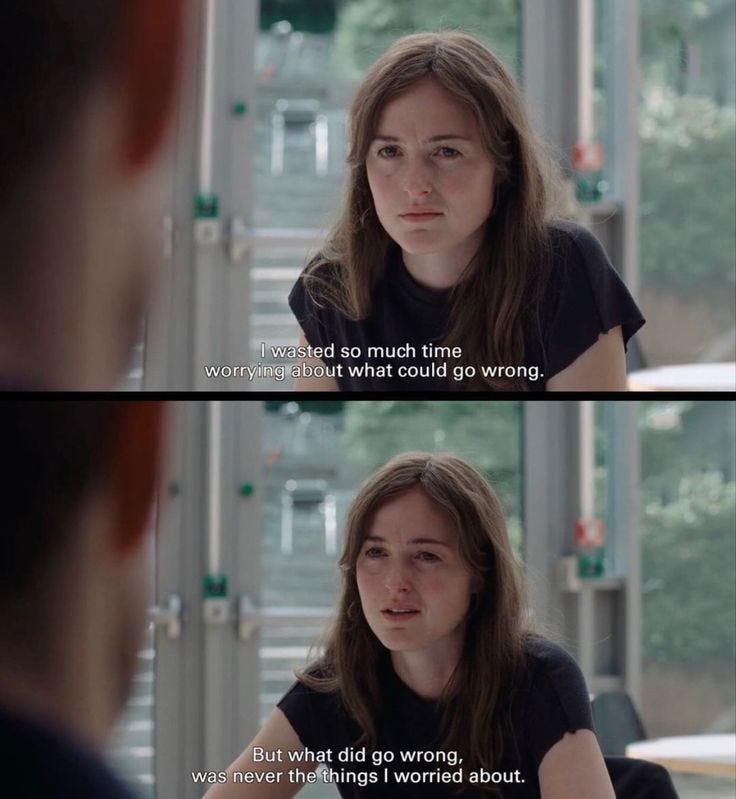

As I enter a new phase of my life where I have nothing grand to pine for and leave to my future self to worry about, I am trying my best to remember that this is all brand new, and that I could not possibly predict how this will turn out because it has never been now before. Even if I know that there are behavioral patterns so deep-seated in my brain, this experience is still new and this is a chance to take more action, to be more assertive in pursuing what I want, or finding out what desire could mean to me years from now. It is so, so scary to surrender, to avoid obsessing over what could go wrong and how I could remedy it even if it hasn’t happened yet. But then I rewatch BoJack’s attempts to live with the horse/man that he is and the latest epiphany I’ve had about his arc is similar to what Julie goes through in The Worst Person in the World: none of the things either of them worried about ever happened, because the things that went wrong were things they didn’t even consider in the first place.

This idea would have haunted me if I learned about this in my early 20s, because then I would spiral and think of all the unlikely ways that things could go wrong on top of all the likely ways that things could go wrong. I’m lucky that I’m learning this at a time where I have more faith in my ability to make the most out of whatever experiences I find myself in, whether I like what I’m going through or not. BoJack’s life is often used as a cautionary tale for people who keep pushing it, but I see his story as confirmation that ‘right’ decisions we make are not simply based on our moral compass (although this would be the top criterion in issues on ethics). The goal in choosing which path to take is not just to pick the most objectively correct decision that everyone could praise you for doing, or the one that you are convinced would make you happy for good. It’s about taking our own desires into account, even if we are unsure of how much we would still want it down the line, and making the choice that builds enough trust in ourselves so that, regardless of the outcome, we are able to live with the consequences. It’s so much easier to deal with the consequences of our actions when we are more deliberate, more present in our decision making. All we really have is now.

S01E11: Downer Ending

S01E01: The BoJack Horseman Story, Chapter One

S01E02: BoJack Hates the Troops

S06E11: Sunk Cost and All That

Both drugs and alcohol, but the recommended episode for the latter is S06E01: A Horse Walks into Rehab. I find that the last three episodes of the first five seasons depict drug abuse pretty well.

S04E11: Time’s Arrow

In Downer Ending, one of BoJack’s scariest hallucinations is in the set of Horsin’ Around where Ethan tells him to say the line, “This is all I am and all I’ll ever be.”

S02E12: Out to Sea

We are introduced to Wanda in S02E02: Yesterdayland

S04E06: Stupid Piece of Shit

S05E07: INT. SUB

I guess this is my cue to watch BoJack Horseman! :D

Thank you for writing this, parts of it are so so relatable!